Kevin Cooley, Photo by Brian Berman courtesy of Kopekin Gallery

The beauty of art is that it’s baked into the artist. You can’t have one without the other, and they need each other to survive. Such is the case with visual artist and photographer Kevin Cooley, someone who’s driven to process difficult topics through his work, regardless of whether anyone is viewing it or not. This played out in a literal sense when he saw a California wildfire drawing near to L.A. during the 2017 La Tune Fire:

“When that fire came to my house, my first instinct was just to leave. I tried leaving, but then I thought, ‘I have to stay here. I have to photograph this.’ I don’t know how else to process something like that,” he told us. “I had no intention that it was going to turn into something else. For me, I’ve always been going to the fires, and now the fire is coming to me.”

As Kevin alluded to, much of his work has focused around fire recently, and our relationship to it as human beings. But, on a much broader scale, it’s an examination of our relationship to the natural world, for better or worse, and installations, like “Devil’s Churn,” are hypnotic, thoughtful, and sometimes damning studies of what it means to exist on this planet.

In our conversation with Kevin, we talked about his approach to photography and visual art, the public service he’s trying to provide, and why he thinks failure is an essential part of a creative career. Here’s photographer and artist Kevin Cooley.

La Tuna Fire, Photograph by Kevin Cooley

WAG: Was being a photographer always your goal?

Kevin Cooley: I started taking pictures in high school, but when I got to college it wasn’t on the approved list of things that my parents were going to let me do. So, I ended up studying international politics, which I’m not really sure why I ended up doing that. I guess it interested me, but I found everything in that realm was so intangible, there’s never any tactile solutions and problems aren’t really solved. It’s very confusing, complicated, and political, obviously.

Photography, to me, felt very tactile. This is a very simplistic view, of course, but you take a picture and you have the result, there it is, it’s a thing. I did some photography courses in college, and a professor said, “You should be doing this, I don’t know why you’re studying whatever you’re studying.” [Laughs] He convinced me to apply to grad school, and I ended up in New York City to get my MFA at the School of Visual Arts.

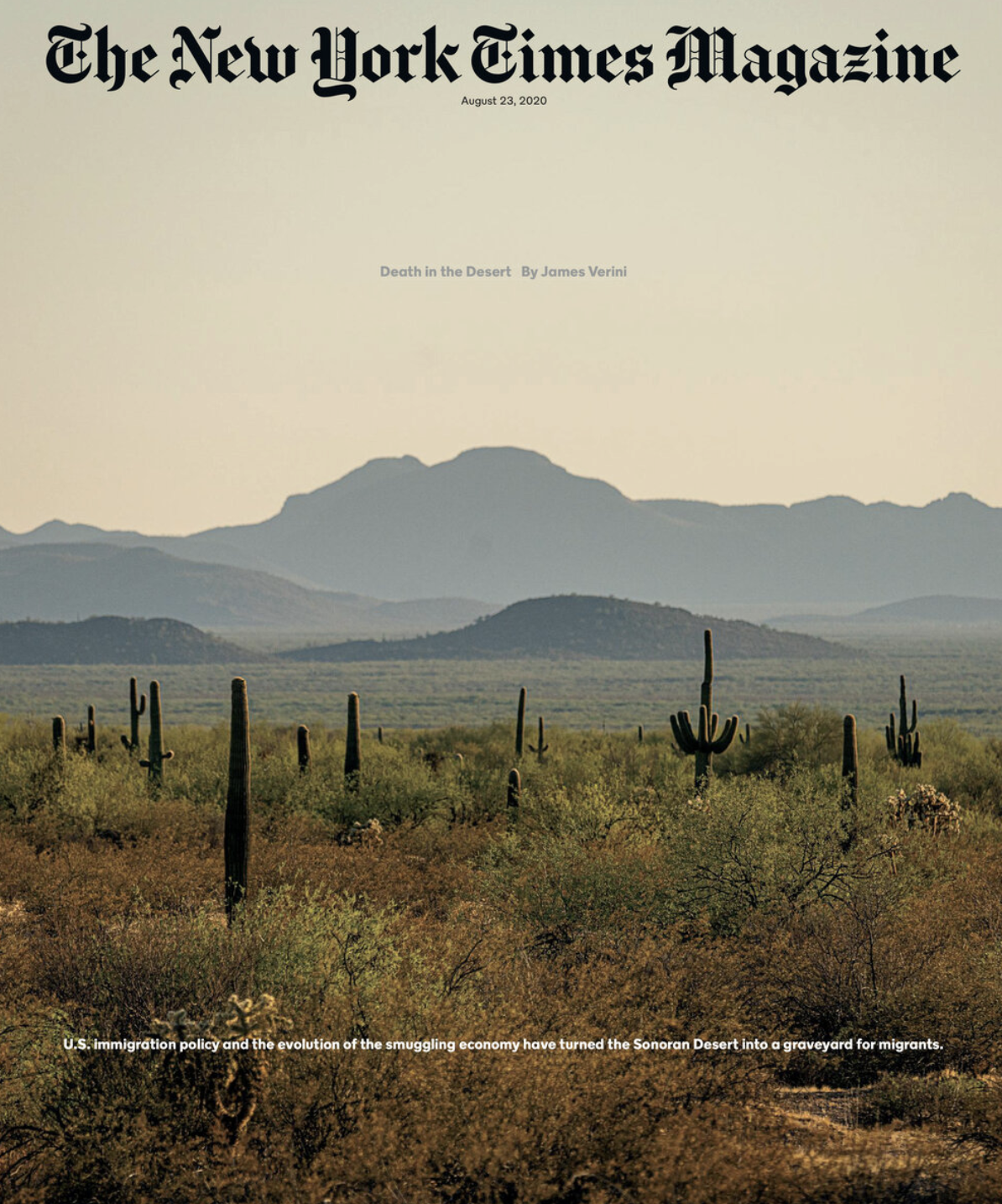

A guy in my cohort, a friend of mine, was doing commercial photography, some stuff for magazines and advertising work in New York. I would help him out and got really excited about that. I never had thought about that before, this idea of working for a deadline and having to produce a photograph. I really like working under the gun, so I started pursuing commercial work and fine art at the same time. I started shooting for Details magazine, which is no longer around, and for The New York Times Magazine.

Photography by Kevin Cooley for The New York Times

Did your commercial work inform your artistic work?

I would say it’s actually the other way around. The commercial stuff has taught me a lot about how to make images. Generally, I would get hired based on my art. Someone would say, “We love this thing you did at this gallery, can you do that for us?” I like to be in both worlds. I don’t do advertising, shoot celebrities or anything like that, but there is a lot of crossover.

The idea that you’d take a picture and it represents something that happened in real time, in a real place, we know that’s not totally true anymore. Not just because there’s Photoshop, but the idea that photography represents truth is also not necessarily the case and that’s been part of the conversation since the beginning of photography.

Regardless of where my work goes, there are certain journalistic standards which I think are important to follow, and most of my artwork—99% of what there is—is in camera. There’s a little color correction if something doesn’t look quite right or I’ll remove a little dust particle that’s bothering me, but it’s pretty much straight photography.

Cooley, behind the camera during a shoot for his Gathering Cloud series.

Which is incredible because some of your images look impossible.

I started a project called “Controlled Burns,” where I made images of these smoke columns in a studio in Nebraska in a big 10,000 square foot studio space. I really like the idea of how in real life, those things are quite small, but you look at them and they look like these giant things. They could be stand-ins for the Dixie Fire that’s burning right now—yesterday there was a 40,000 foot tall fire tornado. These images to me reference that, you know?

“Exploded Views” came out of working with that, and I approached it in a similar manner, although I wanted to find a way to put it more into the landscape. I would find a very safe landscape—I’m not going to set anything on fire—and work with a pyrotechnist to guide me through working with these materials that are somewhat dangerous. I’d set up the scene, light it on fire, jump behind the camera, and photograph it in real space.

It’s playing with scale that’s important to me. Photography can make things seem big or make things seem small, but really aren’t either of those. The word that’s coming to mind is trickery, but that’s not the right word. It’s making it seem more monumental than what it is.

Cooley photographs pyrotechnist Ken Miller while they are working on a photoshoot

Those images make the explosions seem tangible, something that’s instantaneous in reality, but seems like you could hold it.

There’s definitely that, and those things are happening very fast. I have my shutter speed set for some of them at an eight thousandth of a second, as fast as that camera can go. I can only really get maybe one or two of those moments with each explosion that really have an impact and feel substantial. There are a lot of duds when I take those photos.

Exploded View, Magnesium and Aluminum, Photograph by Kevin Cooley

How have recent climate challenges affected your work?

I feel like climate change is the number one problem we’re facing. Almost every other problem seems, in my opinion, to pale in comparison with what’s going on with our environment. Unless we solve that, who cares about anything else? Am I happy about it? No, I’m not happy about it, but I do like that there is plenty of material to work with.

But, how many doomsday articles can you really read? A lot of my work is associated with doomsday articles. There’s an article in Harper’s Magazine in June that a lot of my work appears alongside. There’s just so much and it’s a little bit overwhelming. But, it also makes me think that I should be doing this. I’m able to help reach an audience and hopefully some of this work will make a difference at some point.

A lot of my work, including the fire stuff, is pretty personal. A couple years ago, I moved into the fire zone in this house north of LA and a wildfire came very close to me, about 100 yards away. I left assuming the house was going to be gone. I ended up doing a project that was about bringing these two different interests I had—out of control fires and controlled fires—and how those overlapped in a very tangible way for me.

There’s a cognitive dissonance about living in a place like L.A. or Northern California or wherever, where you are in the fire’s territory. It’s part of the natural landscape and that’s how the ecology continues. In order to be living there, to live in what they call the urban wildland interface, you have to be willing to accept that your house is going to burn down at some point. I would like people to think about that because fire isn’t always necessarily negative. It’s part of the ecology. These forests, the Chaparral in Southern California, the landscape is not going to continue if there’s not fire. It quickly gets into a very loaded conversation about forest management and all that stuff.

I want people to think about fire as both good and bad because we have to find a better way. We can’t just suppress every single fire and expect there not to be mega fires. We have to find a better way. Nobody seems to really know what that is, it seems, but If I can be a part of that conversation in some way, and help people at least think about what their responsibilities are, I’ve done something right.

The Bobcat Fire burns near Los Angeles, Photograph by Kevin Cooley

Is there an element of personal processing that’s going on as well?

Absolutely. If I was not successful at all, I would still be at least interested in photographing things like that. But, I’ve been thinking about doing something other than fire. What’s being shown in Houston right now, there are two pieces centered around fire, and then there’s a film with a pink life preserver being thrown around in this very strange, coastal inlet called the “Devil’s Churn.”

The pink I used in that piece was a stand-in or a surrogate for humanity being thrown around against the natural elements, how the pink is essentially a synthetic, unnatural color. I’ve been thinking a lot about drought issues here in the West, and how to make some work about that, but I can’t figure out how to do something that’s not a news image of a dried lake or whatever. I’m trying to find a new, unique way of representing that. It’s escaped me so far.

Image of Devil’s Churn installed at GreenStreet

Is there generally an element of difficulty in finding inspiration?

That’s a good question. I look back at my work over the last 20 years, and it seems like there’s a very natural progression from each project to the next. I can look back and think, “Oh yeah, I can see why that happened.” As I think through a new project or a new idea, it’s an excruciating process, and it doesn’t feel natural at all. There are plenty of fits and starts. It’s hard to know when something is working and it takes a lot of trial and error.

Right now, I’m in the middle of that turning point. I told myself I wasn’t going to photograph any wildfires this year and then that one came to where I was in the Sierras, and now I want to do more. [Laughs] “Exploded Views” is up right now, and it feels like it might be a nice point in which I can maybe turn my focus elsewhere, artistically speaking.

Does that process frustrate you?

Oh, it’s totally a grind.

Image of Exploded View installed at GreenStreet

Do you wish it was the opposite?

I don’t know, I feel like the grass is always greener. It’s a real struggle, but without that struggle it might not work either. Right now I’m in the thick of it, trying to figure out what to do next, and it’s not always fun. But if it came too naturally, I don’t know if I’d be able to make the sort of leaps I’ve made from project to project in the same way without that difficulty. Does that make sense?

Then again, some of the best projects are from the simplest ideas. I think it can only come out of trying to work on something, and getting it wrong. You’re going to have to have a lot of misfires, a lot of failure, before you get the idea that just works.

Image of Tidal, Installed at GreenStreet